At the moment I’m reading Hannah Arendt’s book “Eichmann in Jerusalem – Ein Bericht von der Banalität des Bösen”. This book and all the history described in it is really… well, I am at a loss for words – horrible, unbelievable, sometimes incredibly absurd, but anyway real. I read up on some names that pop up in the text and that’s how I stumbled on the story of Herschel Grynszpan.

Early Years

Herschel Grynszpan was born on March 28th 1921 in Hannover, Germany. His parent were Polish Jews who had immigrated from Poland in 1911 and settled in Hanover, where they opened a tailor’s shop, from which the family made a modest living. They became Polish citizens after World War I and retained that status during their years in Germany. Herschel was one of six children of whom only three survived childhood.

Hanover to Paris

Herschel attended a state primary school until he was 14, in 1935. He later said that he left school because Jewish students were already facing discrimination. He was an intelligent, sensitive youth who had few close friends, although he was an active member of the Jewish youth sports club, Bar-Kochba Hanover.

When he left school, his parents decided there was no future for him in Germany, and tried to arrange for him to emigrate to the British Mandate of Palestine. With financial assistance from the Hanover Jewish community, Herschel was sent to a yeshiva (rabbinical seminary) in Frankfurt-am-Main, where he studied Hebrew and Torah: he was by all accounts more religious than his parents. But after eleven months he left the yeshiva and returned to Hanover, where he applied to immigrate to Palestine. But the local Palestine emigration office told him he was too young, and would have to wait a year.

Rather than wait, Herschel and his parents decided that he should go to live with his uncle and aunt, Abraham and Chawa Grynszpan, in Paris. He obtained a Polish passport and a German residence permit, and received permission to leave Germany for Belgium, where another uncle, Wolf Grynszpan, was living. He had no intention of staying in Belgium, however, and in September 1936 he entered France illegally. He was unable to enter France legally because he had no visible means of support, while Jews were not permitted to take money out of Germany.

In Paris, Grynszpan lived in a small Yiddish-speaking enclave of Polish Orthodox Jews, and met few people outside it, learning only a few words of French in two years. He spent this period trying to get legal residence in France, without which he could not work or study legally, but was rejected by French officials. His re-entry permit for Germany expired in April 1937 and his Polish passport expired in January 1938, leaving him without legal papers.

In July 1938, the Prefecture of Police ruled that Grynszpan had no basis for his request to stay in France, and in August he was ordered to leave the country. He had no re-entry permit for Germany and in any case had no desire to go there. In March 1938, Poland had passed a law depriving Polish citizens who had lived continuously abroad for more than five years of their citizenship: this was explicitly intended to prevent the 70,000 Polish Jews living in Germany and Austria from returning to Poland, so that path was also closed, so he continued to live in Paris illegally. He was active in Jewish émigré circles and was a member of the Bundist youth movement Tsukunft.

Exile to assassin

Meanwhile, the position of the Grynszpan family in Hanover was becoming increasingly untenable. Sendel’s business was declining, and Berta and Mordecai both lost their jobs. In August 1938 the German authorities announced that all residence permits for foreigners were being cancelled and would have to be renewed: it was obvious that Jews would not be given new permits. Poland, however, said that it would not accept Jews of Polish origin, whom it no longer considered to be Polish citizens, after the end of October. On 26 October, to beat this deadline, the Gestapo was ordered to arrest and deport immediately all Polish Jews in Germany.

The Grynszpans were among the estimated 12,000 Polish Jews arrested, stripped of their property and herded aboard trains headed for Poland. At the trial of Adolf Eichmann, Sendel Grynszpan recounted the events of their deportation, on the night of 27 October 1938: “Then they took us in police trucks, in prisoners’ lorries, about 20 men in each truck, and they took us to the railway station. The streets were full of people shouting: ’Juden raus! Aus nach Palästina!’ ” (“Jews get out! Out to Palestine!”).

When they got to the border, they were forced to walk two kilometres to the Polish border town of Zbąszyń (Bentschen in German). There, however, Poland refused to admit them. The Grynszpans and thousands of other Polish-Jewish deportees were left stranded at the border, fed only intermittently by the Polish Red Cross and Jewish welfare organizations. It was from Zbąszyn that Berta Grynszpan sent a postcard to Herschel in Paris, telling him what had happened and pleading with him to rescue them and arrange for them to emigrate to America – something totally beyond his powers.

Berta’s postcard was dated 31 October, and reached Herschel on Thursday 3 November. The next day was the Jewish Sabbath, and then came the weekend. On the evening of Sunday 6 November, he asked his uncle Abraham to give him money that he could send to his family, but Abraham said that he had little to spare, and that he was incurring both financial cost and legal risks by harbouring Herschel, an illegal and unemployed youth. There was a furious scene, and Herschel walked out of his uncle’s house, with about 300 francs to his name. He spent the night in a cheap hotel.

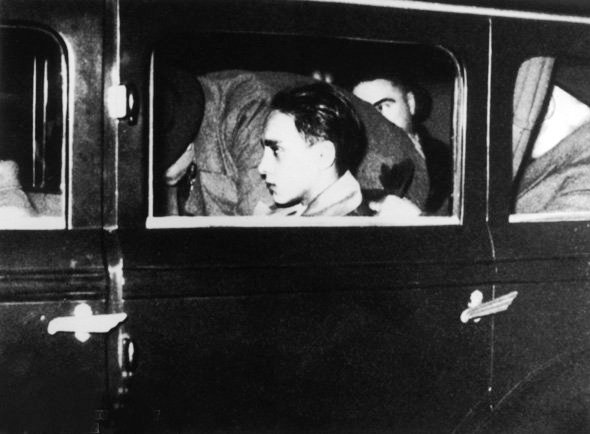

On the morning of 7 November, Grynszpan wrote a farewell postcard to his parents, which he put in his pocket. He then went to a gunshop in the Rue du Faubourg St Martin, where he bought a 6.35 calibre revolver and a box of 25 bullets, for 235 francs. He then caught the metro to the Solférino station, and walked to the German Embassy at 78 Rue de Lille. At 9.45am at the Embassy reception desk, Grynszpan said that he was a German resident and that he wanted to see an Embassy official – he did not ask for anyone by name (an important point in the light of later events). The clerk on duty asked Ernst vom Rath, the more junior of the two Embassy officials available, to see him. When Grynszpan entered vom Rath’s office, he pulled out his gun and shot vom Rath five times in the abdomen. According to the French police account, he shouted “You’re a filthy boche” and said he was acting in the name of 12,000 persecuted Jews.

Grynszpan made no attempt to resist or escape, and identified himself correctly to the French police. He freely confessed to shooting vom Rath (who was in critical condition in a hospital), and again said that his motive for doing so was to avenge the persecuted German Jews. In his pocket was the postcard to his parents. It said:

“With God’s help.

My dear parents, I could not do otherwise, may God forgive me, the heart bleeds when I hear of your tragedy and that of the 12,000 Jews. I must protest so that the whole world hears my protest, and that I will do. Forgive me.

Hermann [his German name]”

quoted from Wikipedia >> read more in

3 Comments

Join the discussion and tell us your opinion.

Ich verdreh mich grad in deinem Blog hier und wollte deshalb etwas hinterlassen:

I love your posts. And I think you’re my intellectual twin.

There. It had to be said. Peas and peace,

G

yay! I have an intellectual twin!!

welcome to my blog!

hast du auch ein blog?

Eher nicht. Also eigentlich schon aber eher was privates zum rumshooten mit friends.

Also nichts wie bei dir!